A sample of some of the items in HRH’s grange collection at the Elmendorph Inn.

By Nancy Bendiner, volunteer, HRH Collections Committee

To coincide with our March 22 Zoom author talk with Dr. Thomas Summerhill, volunteer Nancy Bendiner has taken a deep dive into Historic Red Hook’s Grange collection.

As one travels down Prince Street today, one may notice the unassuming and well kept building at #10 that proudly wears a sign: “RED HOOK GRANGE” in bold red letters, with “No. 918” just below. Built in 1850, according to the Dutchess County Parcel Access records, there have been a few alterations over the years but not many. In those records, it is listed as a “former Village building.”

Left: 10 Prince Street when it served as Red Hook’s volunteer fire department in the 1930s. Right: 10 Prince Street today.

The sign was recently repainted, according to Lisa Ross, whose family purchased the building from the Grange in 2012. The sign stands, she says, as a symbol of what the building has stood for over the years, a building that was once the “people’s town hall.” It was the location of the fire department and ambulance station, until 1948 or 1949. When anyone mentioned the Grange, she said, people knew what that meant and where it was. Though the Grange organization in Red Hook is gone, her family donates the downstairs space so local groups can have meetings, “for the good of the community.” Some of those who have used the space include the Little League and the Red Hook Sports Club. The upstairs space is rented.

The Red Hook Grange, founded in Upper Red Hook in 1902, became an important local institution that focused mainly on the needs of farmers but also sought to answer other community concerns. By 1998, a turning point had been reached where its future was no longer clear. Charlotte Bathrick, longtime Secretary of the Red Hook Grange, wrote a letter to members titled, in capitals, DECISION TIME. She informed them that local Grange leaders recommended the sale of Grange Hall at 10 Prince Street. She hoped the sale would assist the Grange to pay expenses and afford some donations.

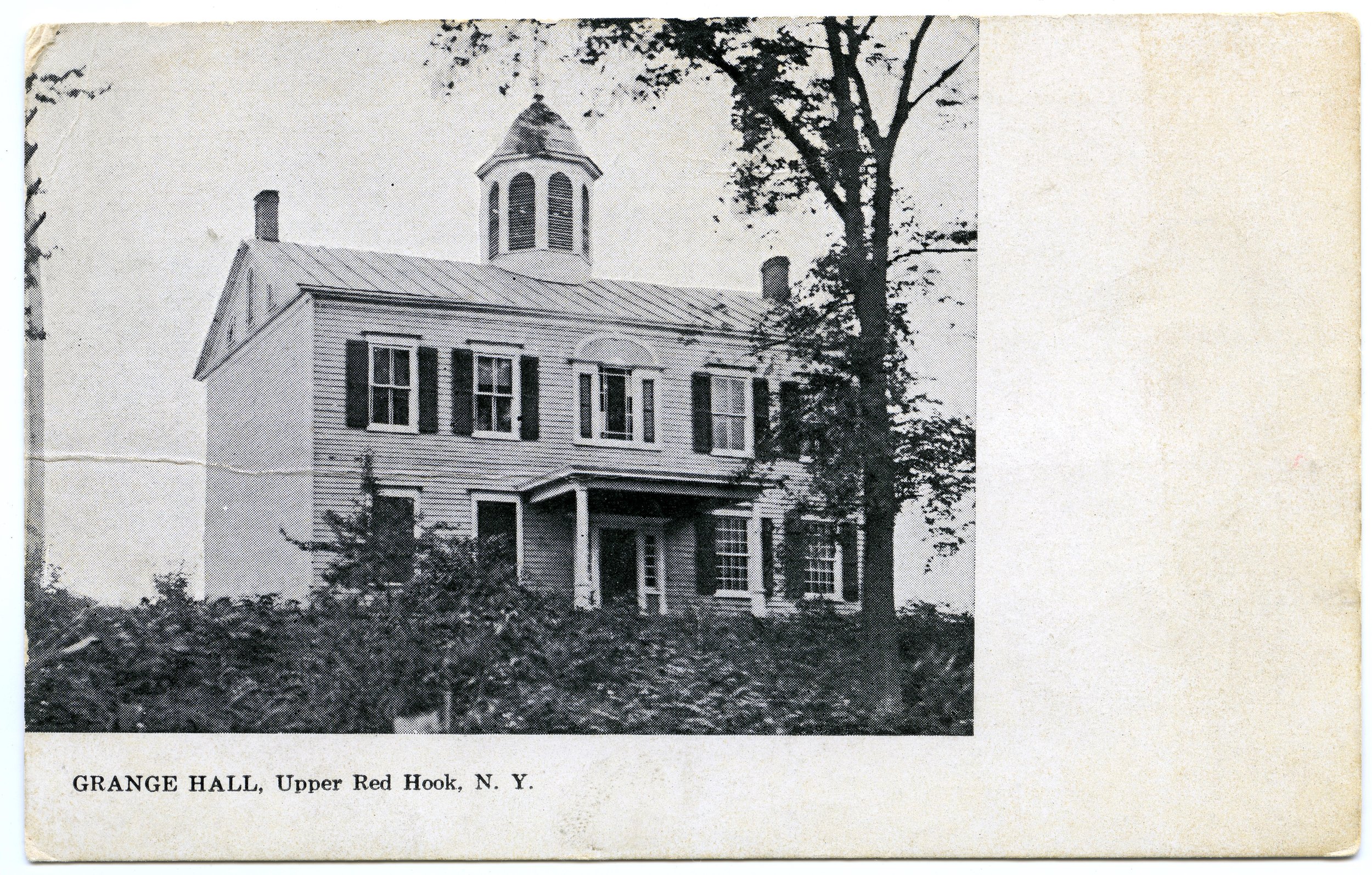

The Red Hook Grange had previously met with adversity. “Hop” Michael (George F. Michael) vividly remembers the terror he felt when at age five he with his sister witnessed the fire in 1954 that “engulfed in flames” the earlier Red Hook Grange building in Upper Red Hook, at Academy Hall. Their home was not far from the fire, and the Academybuilding was destroyed. In 1918, there had been an earlier fire after which the building was rebuilt.

Grange Hall (also known as Academy Hall), Upper Red Hook, built 1918, destroyed by fire 1954.

After the 1954 fire, a meeting was held at Wheeler Hall, in Upper Red Hook, to decide the Grange’s future. Mrs. Curtis Fraleigh offered a new Bible: “This will be our first piece of new regalia since we lost all in the fire.” Before the Grange would officially gain a new permanent home, a number of local buildings would temporarily house Grange meetings and events.

Both Grange buildings were more than structures to the Red Hook Community. Local citizens who remember describe the Grange as the heart of Red Hook.

Born from American History

Nationally, the Grange became the principal organization that represented farmers nationally and locally. It was initially formed in 1867 in Washington, D.C. as the Patrons of Husbandry which soon became the National Grange of the Patrons of Husbandry.

The Revolutionary and Civil Wars both impacted the needs of farmers and how land ownership was structured. According to Leonard Allen, in his History of the New York State Grange, the National Grange “had its beginning through the efforts made by the Federal government to bring order from chaos in the sadly stricken South” right after the Civil War. The Government sought to investigate the “conditions of agriculture in the South as an aftermath of the War.”

Dr. Thomas Summerhill’s book, Harvest of Dissent, Agrarianism in Nineteenth-Century New York, describes the creation of the first New York State Grange in 1868. He also reviews the patterns of land ownership after the Revolution. The social and political trends that he describes are complex. Around the 1840s up to 40% of the farmers in the counties he reviews did not own their own land. They were tenant farmers. Farmers feared they would lose their land, and most held debts.

Thomas Summerhill is a professor at Michigan State University. His book, Harvest of Dissent: Agrarianism in Nineteenth-Century New York, details farmers’ creative and radical organization in the face of social, political, and economic transformations of the nineteenth century. His Zoom talk on March 22 will focus on subjects including the Anti-Rent and Grange movements.

Industrialization, corruption, and the rise of railroads to transport products were perceived as threats to farmers, who feared that capitalists and politicians could destroy the family farm. According to Summerhill’s and others’ accounts, farmers sought to work within their own communities for change, improvement, and survival. The path was not always without disruption and as Dr. Summerhill describes, there was ongoing farmer “unrest”. He writes that the farmers had a political agenda but refused to work through political parties.

Summerhill states “For the Grange, the cleansing of American society was the task of temperate white Protestant husbands and wives who valued hard labor and viewed the traditional family farm as the key ingredient in Republican stability.” Sentiments expressed at the time suggested that “most people” at least at first would be excluded from membership. He cites one commentator who called this the “’irreplaceable racial development’- perfection achieved through the adaption of Anglo-Saxon culture and sensibilities.”

Themes and Principles

The first Red Hook Grange appeared in Upper Red Hook in 1902 when the National Grange Movement was “In its prime,” Claire O’Neill Carr wrote in the Rhinebeck Gazette Advertiser in 1992. There were “tens of thousands of granges dotting the countryside across the nation,” she stated, adding that “almost every small town had its grange hall with weekly meetings devoted, as the national symbol of the sheath and sickle suggests, to promoting the values of the community and rural life.”

The “Purposes” adapted in 1874 by the National Grange were used as a guideline by the local Granges. Written in soaring and patriotic words, a booklet that listed these purposes was distributed to all members. At least some of these purposes survived to different degrees until the Red Hook Grange officially closed in 2007: education as a way to improve crops and products; work within the community; self-discipline and hard work; social activities to maintain the sense of community and expose the young to Grange ideals. Social activities, parties, and dinners continued, as well as outreach to the community, but less active youth involvement happened than in the past. Some commentators say that the Red Hook Grange failed in its last years to adequately maintain goals like these and to grow as the community changed. In her 1998 letter to what was an aging membership, Charlotte Bathrick stated that the Grange membership was no long able to keep up with the work of overhauling and maintaining the Grange building, that only 10 -14 members attended meetings out of 49 members, yet added: “We are all a dedicated bunch.”

A Forward-Thinking Group

Nationally, the 1874 “Purposes'' had unifying goals. The declaration stated near the end: “In essentials, unity, in non-essentials, liberty, in all things, charity.” Members were encouraged as free men to affiliate with any party that will carry out their principles. A last 1874 “Purpose” was stated as well: “Last, but not least, we proclaim it among our purposes to inculcate a proper appreciation of the abilities and sphere of woman, as is indicated by admitting her to membership and position in our order.”

There were a good many political causes supported by the early Grange including the regulation and control of transportation that helped eventually establish the Interstate Commerce Commission in 1887. The Land Grant Act of 1882 that assisted the establishment of agricultural schools, the Farm Federal Loan system, and legislation to give federal aid for states to protect forest and watershed lands were additional Grange causes, among many.

How the Organization Is Organized

A 1967 edition of the Grange magazine celebrating their centennial. This image shows a grange meeting, headed by three women in the position of the “Three Graces” (based on Roman goddesses of agriculture).

The modern Grange has evolved. Ryan Orton, who is an 8th Grade US history teacher in Pine Plains, New York, and also the Secretary of the New York State Grange and Dutchess County Pomona Grange #32, clarifies the organization of the Grange and also puts it in contemporary perspective. The local Granges are subordinate to the State and National Grange in Washington, D.C. “Subordinate” and “Community” Grange are interchangeable terms. The local Community Granges are under the ”auspices of the Dutchess County Pomona Grange, which is the county level” of the Grange. The Pomona or County Grange purpose is “assist the local Granges with their county” and “promote legislative and community work in each Community Grange,” he explains.

As listed in the February 1992 Red Hook Grange yearbook, officers have included Master, Overseer, Lecturer, Assistant Lecturer, Chaplain, Treasurer, Recording Secretary and Financial Secretary, Steward, Assistant Steward, Lady Assistant Steward, Gatekeeper, Ceres, Pomona, Flora, Flag Bearer, and Pianist. Of the positions, ten were held by women that year. Other positions that were not mentioned in the yearbook, are those of the three Graces, who are based on Roman goddesses of agriculture according to Orton. He says that the operational officers included the Master/President (interchangeable names) and the Overseer/Vice President (interchangeable names), as well as Secretary and Treasurer, but that the other positions noted above were mostly ceremonial.

Many people served in their respective Granges. Standing committees have included executive, sunshine, legislative and tax, publicity, membership and youth. The Red Hook Juvenile Grange was organized in 1924. Other local Granges that were founded included Rhinebeck (1900), Rock City (1904), Hyde Park (1907), and Poughkeepsie (1908).

The Grange Within and For the Red Hook Community

According to Orton, the Grange was the original social organization in a community, besides the church: “Granges gave people, especially isolated farmers in the days before modern transportation, a social outlet for discussions, forums, entertainment, dinners, dances, plays, etc. It gave them something to do outside the home, and it helped them meet their neighbors because there was nothing else to do but work on the farm.”

Locally, one yearly highlight of Grange community involvement was the Dutchess County Fair. Roger Leonard in his book, Upper Red Hook, An American Crossroad, quotes a local citizen who said that when the Dutchess County Fair was on, “everything closed up…Everybody went over to the Fair…” News articles frequently commented that for yet another year the Red Hook Grange was the victor again in the competition for best display among exhibits of other Granges. Red Hook was known for its competitive edge. For example, one year, county granges competed on who could present the best play at the Fair; the winner was the one-act play “Cabbage” by the Red Hook Grange.

1992 Winning Grange display at County Fair

Albert Trezza, an attorney who worked for the Red Hook Grange for many years, recently shared his memories of the Fair. Each town had a Grange committee that judged the exhibits. Both he and Pam Hoffman, with whom I also spoke, remember that at one time there was one building at the Fair entirely devoted to Grange exhibits. He adds that when he was a kid, in the 1940s, “there were more cows than people” and some people were still using horses on the farms. He went to the “pinochle” nights and card nights at the old Grange building in Upper Red Hook.

Community was integral. For a Red Hook Grange member, there were certain perks. The New York State Grange offered, for example, medical and dental insurance, supplemental social security insurance, life insurance and estate planning services. There were also programs that could discount expenses on farm needs such as on seed, twine, and fertilizer.

The Red Hook Grange recognized local groups for their accomplishments, such as the Red Hook Rescue Squad among many others. Local families could also receive an award if they helped local organizations. There was also a Citizen of the Year award. Red Hook Grangers attended the meetings of other Granges as well, which was also reciprocated. Sometimes more than one Grange presented an event together.

The Grange took up multiple causes. During World War II, a Red Hook Advertiser article featured the Grange’s part in the national effort to help in the War. There was a “scrap” drive that “will put your town on the map for real war action.” “Eighty percent of the nation’s scrap is in the country…so this is a job for us right here in Red Hook, not our city Cousins.”

Both Grange Halls provided space for community groups, projects and even businesses. In 1964, the Prince Street location was the home of “Lucille’s Dance Studio” where classes were held weekly in tap and ballet. Over the years, meals were held to benefit local organizations, including the Red Hook Little League, and the building was used as a site for voting in elections.

Sources of Revenue

There were multiple revenue sources that kept the Red Hook Grange alive: donations to the Grange; rental income (probably from renting parts of the building to various groups and causes), fundraisers such as rummages and auctions, and sales of various items, such as “tea” or food. Parties and other social events brought in revenue, such as a card party that earned $422.80 in 1956! Meanwhile, prizes for exhibits brought in money. That year, the Red Hook Grange First Place finish at the Dutchess County Fair won $154.50. So far, I have not found evidence of grants from other organizations. Members paid dues as well. In a 1913 “Dues Record,” each member paid 50 Cents each quarter of the year. By 1956, yearly dues were $2.50.

After the rented Grange Hall in Upper Red Hook was destroyed by fire in 1954, much revenue went to a “Building Fund” in an effort to save enough money to purchase a new Hall location.

Meetings and Events

Red Hook Grange Dedication Plaque, June 9, 1961.

The Grange meetings in Red Hook rotated between business meetings and social meetings. Meetings often included a lecture, music, possibly a drama performance if a social meeting, demonstrations and exhibits, and always a covered dish dinner. There was often discussion about the political concerns of the day.

According to Orton, “A century ago, Grange meetings would start at 8 p.m., after chores on the farm were done, and would go until 11 p.m. or midnight…..Then the farmers would go home and get up at 4 a.m. the next morning to do chores once again!”

The initial official event at the Prince Street location was its dedication as the new Grange Hall on June 9, 1961, although it appears the hall had been used at times for several years. The main speech at the event was given by the New York State Grange Master. He asked whether it was a better idea to give college students low interest loans rather than grants, in contrast to a state legislative bill making financial gifts to state students—“Is this a way to make people self reliant?” he asked. This address highlighted perhaps the tendency of the Grange to go its independent way from time to time, as well as the theme of self-sufficiency.

In the HRH Archives collections about the Red Hook Grange, there are some directives and forms that were sent from the National Grange. Some of these provide templates about how to hold meetings, with reference to the order of events, agendas, roles of officers, and what could be considered rituals. The extent to which the Red Hook Grange adhered to the templates about meetings is not entirely clear. The forms and suggestions at least imply that higher levels of the Grange kept up communications with the Red Hook Grange and had a part in defining how meetings were carried out at the local level.

One of the templates sent to the Red Hook Grange many years ago from the National Grange identifies, for example, where officers were to stand and what to say at the start of meetings. For example, the Master was to say: “Patrons and Friends of the Grange, the house for opening this meeting has arrived and each officer will repair to his or her allotted station. Worthy Overseer have all of our friends and neighbors been made comfortable?”

Keeping Grange History Alive

Orton describes the Grange as a “fraternity” similar to the Masons with similar types of ceremonies. Many of the early Grange founders were also, in fact, Masons. He adds that there are a lot of traditions and rituals still in the Grange “to help members understand why things are done the way the are in the Grange. It helps explain who we are, why we were started, and keeps our history alive.”

He says that meetings called Degrees were ceremonial, open only to members, and sought to help Grange members stay in touch with basic life lessons that the Grange often historically espoused such as hope, charity, perseverance, acceptance, etc. The first four Degrees were based on a season; local Granges were in charge of these. The next three Degrees, the Graces, were based on Roman Goddesses of Agriculture, and higher level Granges were in charge of these.

Some commentators over the years have suggested that there were “secret” rituals during Grange meetings, such as passwords and knocks. Mr. Orton offers a context from which these theories may have sprung. He says that a major goal of the Grange in the nineteenth century was to combat the railroad monopolies and their high shipping rates. “Grangers wanted to keep the nosy railroaders and their cronies out of meetings where they were discussing how to fight them and their very unfair business practices.” The passwords and knocks were only known by members and prevented unwanted visitors. He adds that “any connotation as a ‘secret organization’ can start incorrect information that alters the story or purpose of an organization”. There were some ceremonies for members only, such as the “Degrees” ceremonies. As a result, the connection with being a secret organization continued.

A representative from the New York State Grange, Brother Pitcher, spoke in 1956 at the Red Hook Grange about “Ritual Work.” According to the Secretary’s minutes, he pointed out “some of our mistakes” and “stressed the importance of good ritualism.”

The role of religion in ceremonies today was also clarified by Orton. He says “none of the Grange ceremonies are religious, but there are Bible verses included in the ceremonies, with an open Bible at each Grange meeting or other religious texts in the presence of non-Christian members.” There is also a nondenominational prayer at the start and end of meetings.

Bandoliers, a type of sash, were worn for different occasions, as noted by Richard Coon in his hand-written note found in the HRH Archives. Persons with different roles, such as the gatekeeper, overseer, etc. would wear their own bandolier. Two sashes, a red and a blue, were worn on patriotic occasions.

Play called ‘Sardines’ produced by the Grange, date unknown.

Entertainments at meetings of the Red Hook Grange varied, and often reflected interests or trends of the times. These meetings are often described in press accounts that are available for access online, but a limited review is offered here.

In 1922, a meeting included a play with Gilbert and Sullivan operetta selections. In 1949, a Western and Hillbilly Show presented a radio group, the “Down Homers”- Shorty, Cookie, Guy, Rusty and Hank. Those attending a Red Hook Grange flower show in 1974 were entertained by a barbershop quartet from the local Senior Citizen’s club.

Over many years, there were “hobby” nights as part of a Recreational Night. The exhibition of hobbies could include keys, buttons, stamps, slides, arrowheads, and bird houses. There were often card games and prizes even for “non-players” of games. There were occasionally flower arranging contests.

Informative lectures covered a broad area of interest for the Red Hook Grange. In March,1932, members heard lectures from two opposing views of Prohibition. In 1940, John Losee showed pictures of apple farms along with an exhibit of different forms of apple packaging. In 1945, there was discussion about home safety and fire prevention. In 1980, members from several Granges attended a presentation on “Grange” legislation. In 1996, there was a talk about how to restore original storefronts.

Women Gain Rights

As noted in the founding principles of the Grange, women were recognized for an ongoing role. Women’s suffrage was in particular a cause that Grange members supported. In 1914, the Red Hook Grange held a debate: “Resolved: the women of Red Hook Grange favor equal suffrage”.

The elevation of women in the Grange to more influential positions took time though. Women held many officer positions, though the first woman Master of the Red Hook Grange, Johanna Moore, was not appointed until 1992. That year, of the 406 Granges in New York State, more than 100 were run by women. According to Orton, the Grange was “the first organization besides the Church to allow women as equal members with a voice and a vote, and there are four specific offices that must be held by women.”

Youthful Members

In Red Hook, the Juvenile Grange started in 1924. The hierarchy of officers was similar to that of the adult grange, but with an added “assistant juvenile matron.” Most of the meetings were social in nature- there were masquerade dances, dramatic productions. Other meetings had an educational component, such as demonstrations on how to properly salute the flag, chaplain’s night, farmer’s exhibit night, and degree work.

The number of young members eventually started to fall. In 1947, The New York State Grange Deputy’s Report on the Red Hook Grange stated there was no Juvenile Grange at that time: “Too many other activities in the community, especially at Central School.” As adult membership fell, families did not as often attend Grange events together. Cora Marie Shook said in 1987: “I spent three years trying to start Junior Granges in Dutchess County, but we were up against a wall.” Yet some Youth Activity was mentioned in the Red Hook Secretary’s notes in the 1990s: “Nine Grangers went to Bangall for Rural Life Sunday” at a church there and “then on to Stanford Grange for smorgasbord.”

What Happened to Red Hook Grange #918?

The Red Hook Grange officially closed in 2007.

At a typical meeting in the 1920s, according to the Secretary’s notes, there could be sixty or more members present, plus several guests.

Family names in the early Red Hook Grange were well known in Red Hook over many years and included Bathrick, Budd, Coons, Dedrick, Fraleigh, Shook, Greig, Hamm, Teator, Van Steenberg, Wilken, and many others.

In the early 1950s, the membership of the Grange, then located in Upper Red Hook, was 300 and included “practically every farmer and their family” according to Harriet Gallagher Norton in the Rhinebeck Gazette Advertiser. In 1956, membership totaled 179: 104 “brothers” and 75 “sisters.”

By the 1980s, there were about 102 dues-paying members, but the average age of the 30 “active” members was 65. Some lived in other states by then, some found it hard to travel.

Recently, I visited Hoffman’s Barn in Red Hook. While there, I spoke with Roger and Pam Hoffman about their recollections of the Grange in Red Hook. Coincidentally, that day some small wooden buildings, the size of large doll houses, were on sale at the Barn. These structures were once central to many Red Hook Grange exhibitions at the Dutchess County Fair- as seen in a number of photos in the HRH archives. Mr. Hoffman said that he had acquired them as part of an estate. I felt at that moment as though the story of the Grange had almost come full circle, symbolized by these relics which no longer played their central role.

Replica of grange building, for sale at Hoffman’s Barn.

Mr. Hoffman said that farms were originally much bigger and changed hands, parts of the lands were sold off over the years and not used for dairy farming any more. One can still find infrastructure on the lands in Red Hook that supported dairy farms- silos, and farm buildings designed for robotic milking machines- but these are not used.

Those I interviewed presented a few explanations for the demise of the Grange in Red Hook, and no doubt they are all valid.

According to Orton, “Granges that are existing today had to modernize with the times and find ways to fit into their communities by filling a niche that another group doesn’t already fill, especially as the number of farms continues to dwindle.” He adds that the Grange is not just agricultural anymore, though the Granges still advocate for the farmers. Over time, he describes a scenario that we have seen started in the twentieth century especially- but that now appears to take on a stronger part and continues in the Granges that exist today- such as the improvement of “education, health, conservation, transportation, etc.” The Granges still advocate for rural life and the people in rural America.

Many observers have commented that in the pace of modern life, many people have less time and interest to give to the type of events the Grange offered. Pam Hoffman says that volunteerism diminished, with an impact on the Grange.

Orton comments that the Red Hook Grange “found it difficult to modernize and fit into a developing and growing community.” He spoke to previous members of the Red Hook Grange who are now members of his local Stanfordville Grange who felt that the choice was made in Red Hook to favor “quality over quantity” as the growth of new members was not adequately pursued. As membership “dwindled,” the Red Hook Grange did not request help, and “it was like the members literally closed the door to the former Grange Hall on Prince Street and never returned.”

About thirty years ago, according to Albert Trezza, the Red Hook Grange increasingly took in fewer members and continued to go on with just a few people. The motivation lagged to keep on with commitments, such as running the Red Church Cemetery. In the end, Mr. Trezza says, “There was nobody left.”

More than one commentator has suggested that there was a “close-mindedness” about taking in new members. Whether that meant there was more selectivity in acceptance of members is not clear. Up until the 1980s though, Red Hook’s Grange was known for its efforts to recruit members.

Patsy Vogel recently shared her perspective on what happened. She and her family lived on a local dairy farm, and reasons built up to leave. In the mid-1980s, the price of milk was going down but expenses were going up. The Federal government’s dairy “buyout” in the 1980s affected the dairy farms. IBM came to the area with better wages and benefits, even for lower level employees, than the farms could offer. “Women’s lib” she felt also contributed to the trend, as more women worked outside the home.

A Sense of Spirit Lives On

The privately owned house at 10 Prince Street, once the heart of the Grange, continues to offer a sense of the spirit with which the Grange was founded as it offers space to the Red Hook Community and with its sign in front, announces its connection to Red Hook history.

Meanwhile, the Rhinebeck Grange continues, and there are still meetings and a website. Roger Hoffman offered reasons for this survival: “The snack bar at the County Fair helped sustain Rhinebeck Grange financially and gave them purpose; meanwhile strong leaders” wanted the Rhinebeck Grange to endure. The issue of how and why the local Granges lived or died is a worthy question which deserves further investigation.

Postings appear today in local newspapers about the meetings and events of active Grange meetings in Dutchess County- such as in the Community Calendar of Northern Dutchess News. Orton reports that ongoing Granges continue to contribute to their communities. He says that the Dutchess County Pomona Grange, now 125 years old, continues to be active and works with ten local Granges as well as Putnam and Westchester Counties. There are over 350 members in Dutchess County, and meetings are quarterly.

In 1992, a Red Hook Grange yearbook offered some thoughts about the Grange: “If your Community or Grange does not meet with your approval, don’t complain – attend your meetings regularly, and bring your ideas and suggestions where they will be heard and carried out. Be proud of your Grange membership – see you at the first meeting.”

Nancy Bendiner | Historic Red Hook Collections Committee

Thank you to the following: Ryan Orton, Albert Trezza, Lisa Ross, Pam and Roger Hoffman, George F. Michael, Patsy Vogel, and Claudine Klose

For further information about the Grange, please refer to the books noted in sources, Historic Red Hook’s archives at the Elmendorph Inn, as well as digital newspaper archives accessible through news.hrvh.org, and fultonhistory.com

Books and Publications

Alexander, L. Ray and Leonard L. Allen. 100 year History of the New York State Grange 1873-1973.

Arthur, Elizabeth. The History of the New York State Grange 1934-1960.

Leonard, Roger M. Upper Red Hook: An American Crossroad.

Summerhill, Thomas. Harvest of Dissent: Agrarianism in Nineteenth Century New York.

Sources in HRH Archives:

“Brief History of Rock City and Grange,” 1938.

Rock City Juvenile Grange,1931.

Multiple Red Hook Grange yearbooks and pamphlets.

“Grange” magazine.

“Declaration of Purposes”, booklet, National Grange.

Grange Collection donated by members of the Rock City Grange via the Pomona Grange

Richard Coons Collection on Red Hook Grange,

“Suggested Form for an Open Grange Meeting”, The New York State Grange.

Newspapers:

“Red Hook Times” in the Rhinebeck Gazette Advertiser

Kingston Daily Freeman

The Register-Star, Hudson, New York

Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle-News;